The European Commission announced last Wednesday a new package of proposals designed to reform the EU asylum system. The proposals include compulsory redistribution of asylum applications among the EU member states. This is called ‘corrective allocation mechanism’ or ‘fairness mechanism’.

Countries would be allocated ‘reference shares’ of asylum applications, and the moment a country’s reference share is exceeded by 50%, an automatic system will set it that will send the excess asylum applicants to countries that have not attained their reference shares yet. If member states do not cooperate, they will have to pay a ‘solidarity contribution’ of €250,000 for every asylum application they refuse to process.

The proposal for compulsory redistribution backed by the threat of financial penalties (sorry, solidarity contributions) is very ambitious. But can it work? And I mean, can it work in a strictly technical sense, provided that the EU musters the political support to adopt the proposals[1], manages to make the member states comply with the rules, ensures that they don’t game the national asylum statistics, and so on – additional problems that are by no means trivial to solve. Let’s also leave aside for the moment the normative issue whether such a compulsory redistribution system is fair, to asylum seekers and to the EU member states. For now, the simpler question – can the system work even in the best of political and bureaucratic circumstances?

How is the system supposed to work?

This is how the system is supposed to work, or at least how I think it’s supposed to work, based on the available explanations (see here, here, here and the actual draft regulation here):

(1) Each country gets a ‘reference key’ based on the relative size of its population and the relative size of its GDP (the two factors weighted equally) compared to the EU totals. For example, in 2014 Germany had a population of 81,174,000 (16% of the EU population of 508,191,116) and a GDP of €2,915,650 million (21% of the EU GDP of €13,959,741 million[2]), which, when combined, make up for a reference key of 18.5%.

(2) This reference key is translated into reference shares (indicative shares of the total number of asylum applications[3] made in the EU that each member state is expected to receive) by multiplying the reference key with the total numbers of asylum applications registered in the EU in the preceding 12 months. For example, according to Eurostat[4], between 1 January 2014 and 31 December 2014 the total number of asylum applications received in the EU was 653,885, so Germany’s reference share for January 2015 (covering the period 1 February 2014 – 31 January 2015) would be 18.5% of 653,885 which equals 120,969 applications.

(3) If a member state receives a number of applications that exceeds by 50% its reference share, the excess applications are to be redistributed to member states that have not attained their reference shares yet. For example, Germany would have to receive more than 181,453 (150% of 120,969) applications during the current and preceding 11 months to trigger the relocation mechanism.

(4) The reference totals and references shares are updated constantly and automatically.

How would the system work if it had to be implemented at the end of 2015 already?

Let’s first do the simple arithmetics to see how the system would work if it had to enter into force in the last month of 2015. We can plug in the total number of asylum applications registered in the preceding 12 months (hence, between 1 December 2014 and 30 November 2015) to calculate the country’s reference shares. We can then see who did more and who did less than their fair (reference) share, and we can estimate the number of transfers that would be necessary to balance the system.

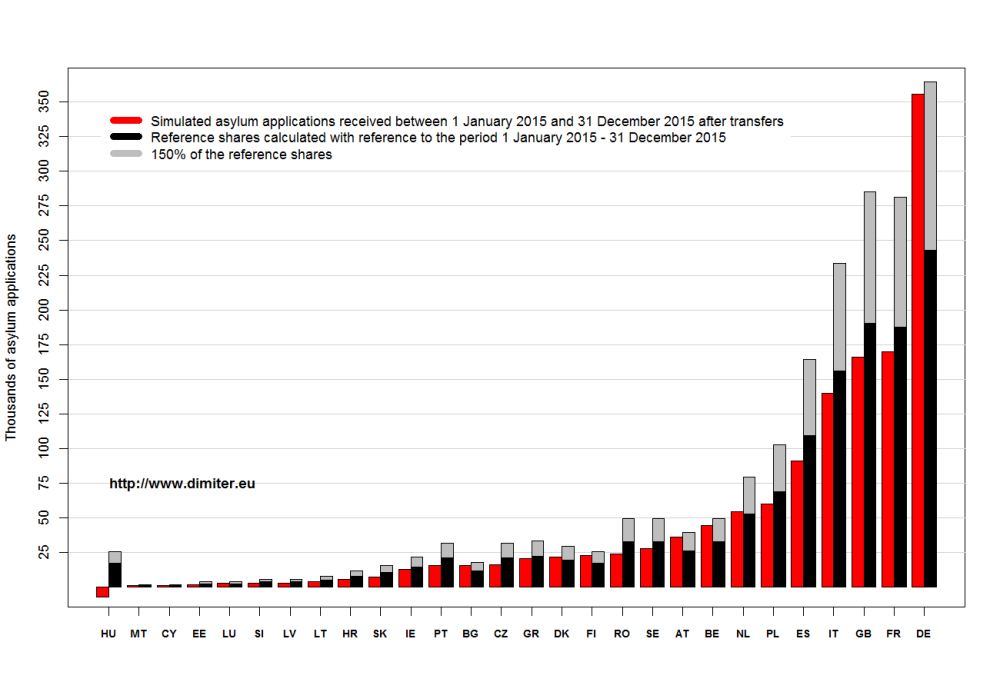

According to Eurostat, the total number of asylum applications received in the reference period was 1,281,560, so this number is used in the calculations that follow. The figure below shows the reference shares (in black), 150% of the reference shares (in grey) and the actual numbers of applications received during the entire 2015 (in red). We can see that Hungary, Sweden, Germany, Austria, Finland, Bulgaria, and Cyprus would have exceeded 150% of their reference shares. And between them they would have had 449,821 ‘excess’ applications for redistribution. All the other member states are potential recipients (with the exception of Belgium, Denmark, and Malta which have received numbers of applications exceeding their reference shares but with less than 50%). The total number of available ‘slots’ for transfer is 592,469. The UK has 145,750, France has 106,227, Spain has 91,589, Italy has 67,689, Poland has 54,456, and so on. Even Greece would have to accept 8,577 more applications to achieve its fair share of registered asylum applications[5].

To sum up, if the ‘fairness mechanism’ was to enter into force in December 2015, it would require the relocation of almost half a million asylum seekers across the continent, with some member states having to receive more than 100,000 additional applications to balance the system. More than one-third of all applications received in the EU during the preceding 12 months would have to be relocated.

If the UK[6], for example, would refuse to accept the additional asylum applications to fill up its reference share, it would be expected to pay ‘solidarity contributions’ to a maximum of €36,437,500,000 (more than 36 billion euros). (For comparison, the total gross UK contribution to the EU budget in 2015 was around €16 billion). The total pool of asylum applications to be relocated would be worth €112,455,250,000 (that is, more than 112 billion euros)! For comparison, the total budget of the EU for 2015 was € 141.2 billion.

To my mind, the scale of the potential fines (sorry, ‘solidarity contributions’) is so big as to make their application totally unrealistic. Of course, it is the threat of fines that is supposed to make the member states cooperate, but to do their work, fines still have to realistic enough.

To sum up the argument so far, things don’t look very bright for the solidarity mechanism. But one might object that 2015 was exceptional, and that it is precisely this type of imbalances observed at the end of 2015 that the fairness mechanism is designed to avoid. Yet, unless the system starts with a clean slate[7], the existing imbalances accumulated over the past months would have to be corrected somehow. The analysis above shows the enormous scale of the corrections needed, if the system would have entered into force five months ago.

How would the system handle the 2015 flow of asylum applications?

We can also try to simulate how the fairness mechanism with compulsory reallocation would have handled the flow of asylum applications that the EU experienced during 2015 (provided that the member states cooperated fully). That is, we start with the situation as observed in January 2015, we calculate the reference shares and apply the necessary transfers to balance the system, and then we move forward to February 2015 observing the actual numbers of applications received in reality, balance the system again with the necessary transfers, and so on until the end of the year. (The script for the analysis and the simulation (in R) is available upon request.)

Running the simulation for the entire course of 2015 delivers good news and bad news (for the architects of the proposed mechanism). The good news is that the redistribution system does not get ‘choked up’ – that is, it does not run out of capacity to redistribute asylum applications received by some member states in excess of 150% of their reference shares to member states that have yet to reach their reference shares. The bad news is that in order to get and stay balanced, the system applying the ‘fairness mechanism’ needs to make approximately 500,000 transfers (that makes 37% of all asylum applications received in the EU during the year).

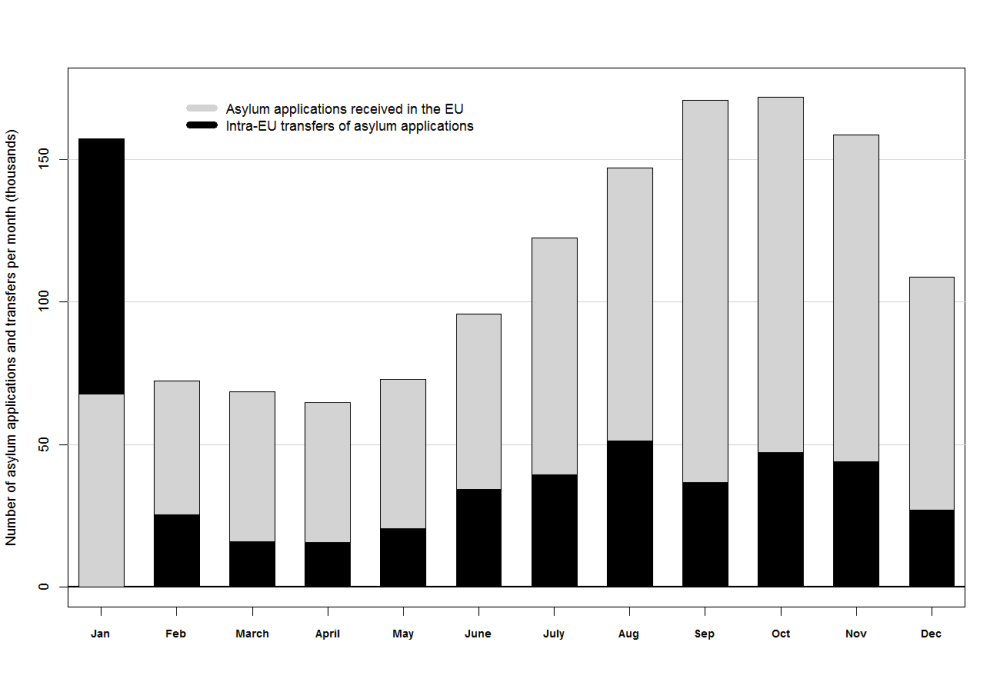

The figure below shows the number of transfers (in black) that need to be made per month, together with the actual number of asylum applications received in the EU as a whole during this period (in grey). Approximately 157,000 transfers must be made in the first month of the simulation (January 2015) to balance the system initially, and the remaining 343,000 are needed to keep it in balance for the rest of the year. The peak is in August, when more than 50,000 transfers must be made. (The bars are not stacked upon each other but overlap).

The next figure shows the distribution of transfers per member state. The blue bars that go below the horizontal line at zero indicate that the member state is a net ‘exporter’ of asylum applications, and the red ones that rise above the zero line indicate that the member state is a net receiver of transferred applications during the year, according to the simulation. (The parts of the bars colored in light blue and light red show the transfers made in the first month of the simulation.)

It is clear from the figure that Hungary, Sweden, Germany and Austria export the greatest number of applications, while Poland, Italy, Spain, France and the UK are expected to receive the most transfers. Some countries actually change their status in the course of the year from exporters to receivers of additional asylum applications (Denmark) and vice versa (Finland). Even Sweden and Hungary – countries that are big net exporters for most of the year have to receive additional applications during one or two months (see here the detailed plot of the experience of individual countries over the 12 months of the simulation).

Despite the huge amount of transfers, not all member states handle a completely proportional burden of the total EU pool of asylum applications throughout the year. While the monthly transfers correct for gross imbalances and ensure that no country deals with more than 150% of its reference share, the system still leaves potential for significant differences across the member states. The figure below demonstrates this fact by showing the simulated number of asylum applications in red (actual applications received and simulated transfers) and the references shares (in black and grey). While the two sets of bars are much closer now, and the red one does not exceed the grey one for any country, member states still vary from fulfilling 70% of their reference shares (for example, Croatia, Portugal, Romania, and Slovakia) to fulfilling close to 150% of their reference shares (Germany, Belgium and Austria).[8]

Conclusions

To sum up, the proposed compulsory redistribution of asylum applications among the EU member states can reduce the current imbalances, but only at the price of a huge amount of transfers between the member states. With the proposed parameters, the mechanism would be able to handle even a great influx of asylum seekers as the one observed during 2015. However, under the 2015 scenario, half a million applications would have to be redistributed to make it work. An enormous amount of transfers between member states would be necessary to balance the system initially (unless the mechanism starts with a clean slate), and as many as 50,000 applications per month might have to be redistributed later (under a scenario similar to the one that actually occurred in 2015).

The reference period of 12 months used for calculating the countries’ reference shares must be updated and moved forward every month to ensure that the system retains enough capacity for redistribution. Otherwise, the ‘cushion’ provided by the fact that countries only export applications once they receive 50% more than their reference shares might not be enough to guarantee that there are enough ‘free slots’ in other member states. For the reference period to be updated fast, reliable and almost instantaneous information about the flows of asylum seekers to all member states must be available. Currently, the latest month for which Eurostat has data on the asylum applications received in all EU member states is December 2015: that is, at the moment, the reference shares can be updated with at least a 4-month lag. This might be too slow to accommodate the rapidly changing flows of asylum seekers to Europe and might quickly grind the fairness mechanism to a halt.

The disadvantage of a relatively short reference period of 12 month that is constantly updated is that some member states might have to receive transferred applications at one point of time and then be eligible to redistribute applications to other countries just a few months afterwards. Such moving around of asylum seekers across the continent is of course highly undesirable, and costly as well.

Although the system might be able to correct the gross imbalances, it might still allow significant differences in the asylum application burden that different EU countries carry to persist. This fact requires attention to the way the ‘excess’ applications are to be distributed among the eligible member states that have not achieved their reference shares yet (since, typically there will be more available slots than requests for redistribution).

Finally, given the scale of required transfers to make the fairness mechanisms work, the size of the proposed penalties (solidarity contributions) for refusing additional applications is so huge as to be completely unrealistic. If under this mechanism member states are potentially liable for amounts that exceed their total annual contributions to the EU budget, there is little chance they will agree to participate in the mechanism in the first place.

All in all, while in principle the proposed fairness mechanism can work to reduce significantly the imbalances in the distribution of asylum applications across the EU, once the member states realize the amount of additional applications they might have to deal with under this policy, it is highly unlikely they will approve it. And certainly not with the current parameters regarding the reference periods, the references shares or the financial penalties.

Notes

[1] The Polish foreign minister already called the proposals an ‘April Fool’s Day joke.’

[2] The population and GDP estimates are based on statistics provided by Eurostat. GDP is in current prices and comes from the ‘tec00001’ database, in particular.

[3] In addition to asylum applications, the system will also take in to account the number of resettled persons. Eurostat however does not provide monthly data on resettlement. And the (annual) numbers of resettlements relative to asylum applications are so low (less than 1%) that we can ignore them in the analysis without much harm.

[4] The monthly statistics on asylum applications are available in the ‘migr_asyappctzm’ database. The version used in the analysis has been last updated on 6 May 2016

[5] Wait, what? Greece would have to receive more asylum applications? That’s right. Although hundreds of thousands (if not millions) of migrants have arrived on Greek territory in the past year and a half, in 2015 the Greek state has registered as asylum seekers only a negligible proportion of them. So, according to the official statistics (that would be used to run the fairness asylum distribution mechanism), Greece would have to register more applications and would be eligible to receive transfers from other member states until it reaches its fair share. I will leave it to you to judge whether this is a feature or a bug of the proposed system.

[6] The UK and Ireland, by the way, are invited but are not required to join the proposed system, even if the rest of the member states approve it.

[7] From the available documents, it does not seem to be the case that the fairness mechanisms will start with a clean state; that is, with a reference period not extending 12 months back.

[8] Curiously, Hungary appears to have made more transfers than actual applications received during the year according to the simulation, due to the huge fluctuations in the monthly amount of applications registered (which average 20,000 in the first 9 months of the year, but then drop to less than a thousand in the last three) and the moving reference period for calculating the reference shares.

Key numbers

Country |

Code |

Reference key |

Asylum applications 2015 |

Reference

|

Excess/deficit from reference shares for 2015 |

Excess/deficit from 150% of reference shares for 2015 |

Transfers to be

|

| Austria | AT | 2,0% | 88.160 | 25.631 | 62.529 | 49.713 | -51.796 |

| Belgium | BE | 2,5% | 44.665 | 32.039 | 12.626 | -3.393 | 0 |

| Bulgaria | BG | 0,9% | 20.375 | 11.534 | 8.841 | 3.074 | -4.676 |

| Croatia | HR | 0,6% | 205 | 7.689 | -7.484 | -11.329 | 5.510 |

| Cyprus | CY | 0,1% | 2.265 | 1.282 | 983 | 343 | -850 |

| Czechia | CZ | 1,6% | 1.515 | 20.505 | -18.990 | -29.242 | 14.694 |

| Denmark | DK | 1,5% | 20.940 | 19.223 | 1.717 | -7.895 | 1.159 |

| Estonia | EE | 0,2% | 230 | 2.563 | -2.333 | -3.615 | 1.838 |

| Finland | FI | 1,3% | 32.345 | 16.660 | 15.685 | 7.355 | -9.319 |

| France | FR | 14,2% | 75.755 | 181.982 | -106.227 | -197.217 | 94.098 |

| Germany | DE | 18,4% | 476.510 | 235.807 | 240.703 | 122.799 | -120.770 |

| Great Britain (UK) | GB | 14,4% | 38.795 | 184.545 | -145.750 | -238.022 | 127.292 |

| Greece | GR | 1,7% | 13.210 | 21.787 | -8.577 | -19.470 | 7.408 |

| Hungary | HU | 1,3% | 177.130 | 16.660 | 160.470 | 152.140 | -184.043 |

| Ireland | IE | 1,1% | 3.270 | 14.097 | -10.827 | -17.876 | 9.674 |

| Italy | IT | 11,8% | 83.535 | 151.224 | -67.689 | -143.301 | 56.460 |

| Latvia | LV | 0,3% | 335 | 3.845 | -3.510 | -5.432 | 2.756 |

| Lithuania | LT | 0,4% | 320 | 5.126 | -4.806 | -7.369 | 3.674 |

| Luxembourg | LU | 0,2% | 2.505 | 2.563 | -58 | -1.340 | 431 |

| Malta | MT | 0,1% | 1.850 | 1.282 | 568 | -72 | -519 |

| The Netherlands | NL | 4,0% | 44.975 | 51.262 | -6.287 | -31.919 | 9.498 |

| Poland | PL | 5,2% | 12.185 | 66.641 | -54.456 | -87.777 | 47.751 |

| Portugal | PT | 1,6% | 900 | 20.505 | -19.605 | -29.857 | 14.694 |

| Romania | RO | 2,5% | 1.255 | 32.039 | -30.784 | -46.803 | 22.958 |

| Slovakia | SK | 0,8% | 325 | 10.252 | -9.927 | -15.054 | 7.345 |

| Slovenia | SI | 0,3% | 275 | 3.845 | -3.570 | -5.492 | 2.756 |

| Spain | ES | 8,3% | 14.780 | 106.369 | -91.589 | -144.774 | 76.221 |

| Sweden | SE | 2,5% | 162.455 | 32.039 | 130.416 | 114.397 | -134.256 |